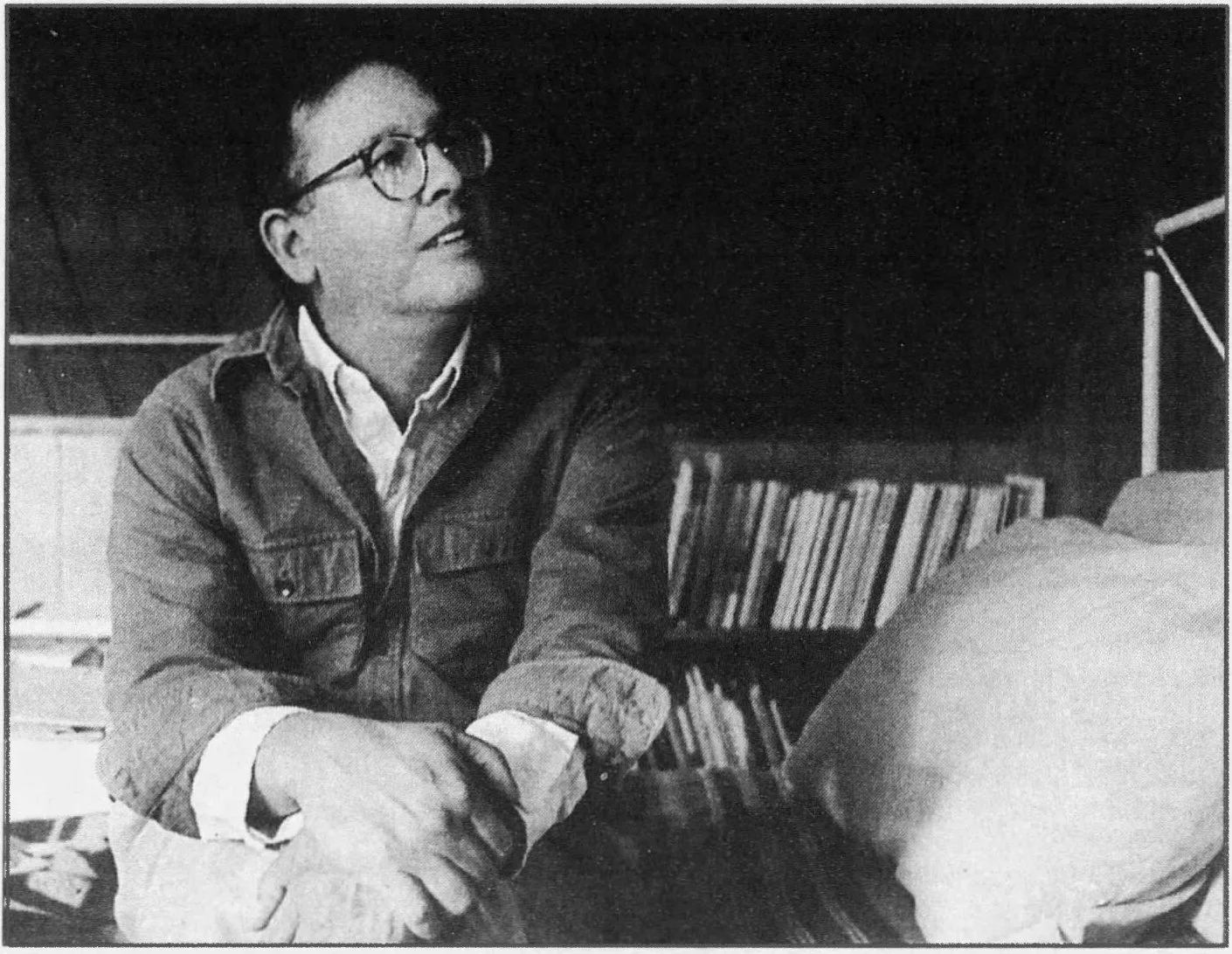

“If you've got the imagination, the talent and the perseverance, if you have stories to tell, and if you possess strong medicine and a little luck, you can be a writer."

- James Welch, “Letter to a Young Writer” (unpublished)

A principal writer in the Native American Renaissance, Welch was born on the Blackfeet Reservation where he spent the early part of his life. His father James Sr., Blackfeet, was a rancher, welder, hospital administrator and, later, a farmer on the Fort Belknap Reservation. His mother Rosella, Gros Ventre, worked as a stenographer for the Bureau of Indian Affairs in the various places the family lived, which included Washington, Oregon, Alaska and Minnesota. Welch began writing in high school, working on poems in study hall and in the evenings instead of homework. By the time he was in his early 20s he had failed out of two colleges and was working as a seasonal employee for the U.S. Forest Service in California, where he continued to write poems in his free time. He was intensely shy, did not recall dating in high school or early college, and spoke only in class when called upon. His early writing was imitative; he copied the poems he loved in longhand and later tried his own versions. In 1964, Welch completed a degree in liberal studies from the University of Montana, beginning work on an MFA in creative writing there the following year under the legendary teacher and poet Richard Hugo. It was during this time Jim met Lois Monk, an assistant professor of English and Comparative Literature at the University of Montana. They married in 1968 and remained together until the end of his life.

His only collection of poems, Riding the Earthboy 40, was published in 1971 and remains one of the major statements of American poetry. Winter in the Blood, published in 1974, received a front-page review in The New York Times. The reviewer called the book a nearly "flawless novel." Welch followed with The Death of Jim Loney in 1979, a stark and unromantic work tracing the course of one man's decline on a Montana reservation during a northern plains winter. In 1986 he published what is widely considered his masterpiece, Fools Crow, a novel about the Blackfeet people at the time of the arrival of the white man, for which he received the Los Angeles Times Book Prize for fiction and the American Book Award. From 1979 to 1989 Welch served as Vice Chairman of the Montana State Board of Pardons, a period of his life that inspired his novel The Indian Lawyer, which was published in 1990. He was co-writer of the 1992 documentary Last Stand at Little Bighorn, which led to his only work of nonfiction, Killing Custer, an examination of the famous battle from the tribal points of view. His last book, The Heartsong of Charging Elk, about a young Oglala Lakota man who travels with Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show in 1889 and becomes stranded in France, was published in 2000. His work has been printed in nine languages.

In spite of his quiet nature, Welch was a popular speaker and respected teacher. He held the Theodore Roethke Chair at the University of Washington in 1976, teaching there several times in the early 80s as well as at Cornell. During this time he was invited by the Carter Administration to a reception at the White House, but was unable to attend because he could not afford the plane fare. In 1995, the French government awarded Welch the prestigious Chevalier de l'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres medal. He was one of five American Indians invited to a Congress of Indigenous Americans sponsored by President Jacques Chirac in Paris in January 1996. The lunch at the Élysée Palace was a major event in his life. Welch also traveled widely across the United States and Europe teaching writing workshops and participating in festivals, reading tours and panels. He was awarded honorary doctorates from Rocky Mountain College, Montana State University and the University of Montana.

Welch died in August of 2003 of a pulmonary embolism at his home in Missoula after a nearly year-long struggle with lung cancer. He was 62. His work, defined by a singular mix of humility, dark humor, quiet power and elegance, stands alone in the pantheon of American letters.